Receiving whatever we ask for is scandalous in an age of consumerism. My son, like so many of us, never stops asking for things. If I gave in to all his requests, he’d quickly make himself sick with treats and would soon be able to recite by memory every episode of his favourite animated series. I’d be a truly irresponsible father. This portrait of an indulgent father probably shouldn’t be the first that comes to mind when we think about God. Perhaps, Christ’s Sermon on the Mount isn’t addressing me and my family — whose material needs are thankfully satisfied — perhaps he has someone less privileged in mind. This subtle shift significantly changes the meaning of the sermon. Suddenly Christ isn’t talking me and mine when he says “ask and you will receive.”

“17 ‘Therefore anyone who sets aside one of the least of these commands and teaches others accordingly will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven.20 For I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven’” (Matt. 5. 17-20).

In other words, if you mess up on the smaller stuff, there will still be a place for you in the coming kingdom of peace. Unfortunately, this isn’t true for everyone. Christ tells us that there’s no place in the coming kingdom for the leaders of Israel, those individuals with real power. To those who abuse their power, Christ offers condemnation alone. This message shouldn’t be all that new to us; Christ often talks about how difficult it is for the wealthy and powerful to enter the kingdom of heaven.

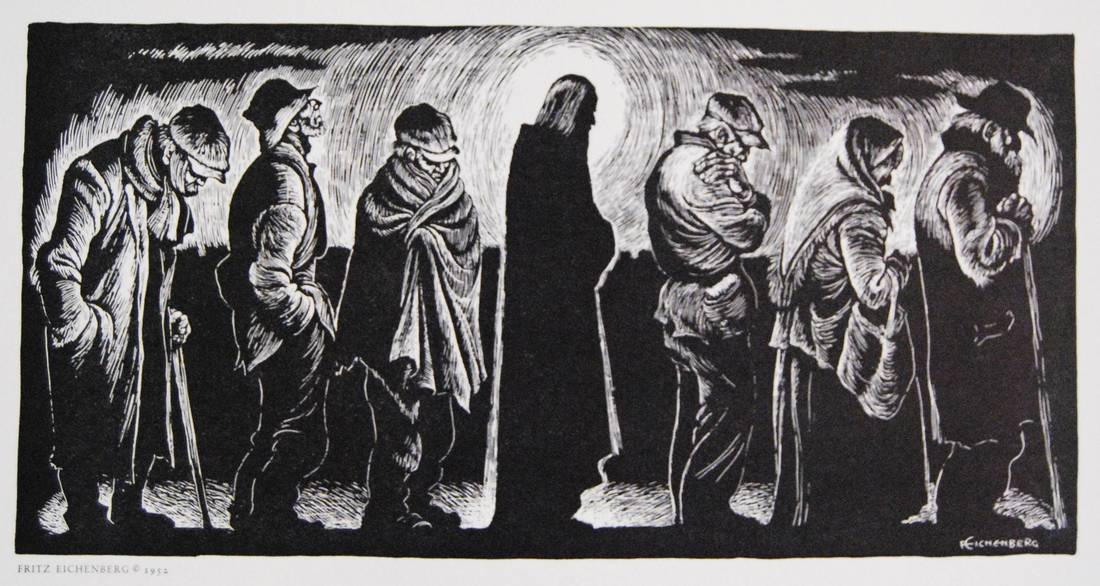

Assuming the Sermon on the Mount’s intended audience is the weak and the suffering is a helpful exercise in bringing new meaning to light. Walter Wink, for example, takes a similar position in his interpretation of Christ’s instructions elsewhere in this same sermon on turning the other cheek and walking an extra mile (Matt. 5. 38-42).*

Wink argues that these teachings don’t advocate for passivity in the face injustice, but instead, are a call for non-violent resistance. Wink explains that striking someone on the cheek was a way a slave-owner, Roman soldier, or husband might humiliate an inferior. Simplifying Wink’s argument, we could say that offering the other cheek is one way an inferior asserts her humanity. Turning the other cheek implies that the persecuted is a human being with agency who will not merely conform to the will of a master. By asserting the other cheek the inferior challenges the humility that accompanies the abuse.

Christ’s teaching to walk two miles when pressed into service to walk one is probably the clearest example of Wink’s argument. During Rome’s occupation of Israel, Roman soldiers regularly forced the poor to carry their heavy packs. By law, however, the soldiers were not permitted to compel anyone to walk more than one mile. Jesus’ audience would know that soldiers could be arrested for breaking the law. Jesus, then, isn’t arguing that his audience suffer the violence of an oppressor passively, but rather to resist injustice in a way that doesn’t replicate the harm.

The wealthy and powerful, ignorant of the daily grind of the lower classes, would struggle to comprehend the meaning of these teachings. Wink’s insight, therefore, lends further support to the assumption that the Sermon on the Mount addresses and is more easily understood by the weak, oppressed, and underprivileged.

The illustration used by Christ in the section of the Sermon on the Mount titled, “Ask, Seek, Knock,” reinforces our argument further. In his example, it’s a son asking a father for bread, not the other way around. I would be diluted and uncaring if I expected my toddler to provide me with my daily bread. By necessity, children need to ask, discover, and knock. These activities require a level of humility and neediness often absent in the life of the powerful. The oppressed, like children, are better equipped to understand Jesus’ message by virtue of their position as oppressed people, not because they chose to oppose prevailing cultural trends.

When you have wealth and power you don’t need to ask for something to eat, you don’t need to apply for EI or take public transit. If you want something, you buy it; if you’re hungry you order takeout; if you’re bored you jump on (or out of) an airplane. As a white male, for example, most doors are open and waiting: this is my privilege.

In Christ’s vision of the kingdom of heaven, there’s lots of asking, seeking, and door knocking. Yes, in the coming kingdom of peace everyone who asks will receive, who seeks will find, and to the one who knocks the door will be opened. It’s just that for some, in the current kingdom, there’s never been a need to ask or search or knock because they’ve always already had everything they’ve ever wanted. In a certain sense then, Christ is right: the powerful, the wealthy, and the leaders and teachers of the law have no place in the coming kingdom of peace.

To the powerful and the privileged like myself: if you’re going to follow Christ, if you want to understand his teachings, you need to find ways to live in solidarity with the weak and the powerless. Either you’re on the side of the oppressed, or you are the oppressor. There’s only room for one of those groups in the coming kingdom of peace.

* Walter Wink, The Power that Be: Theology for a New Millennium, 1998 (p. 98-111).

Caleb Ratzlaff attends Westview Christian Fellowship in St. Catharines Ontario. He spends the majority of each day raising two toddlers. And when he’s not chasing his boys around the neighbourhood, he might be blogging at calebratzlaff.wordpress.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed