Part 2: Mother Mary Revolutionary - By Rosilee Sherwood

“57 As evening approached, there came a rich man from Arimathea, named Joseph, who had himself become a disciple of Jesus. 58 Going to Pilate, he asked for Jesus’ body, and Pilate ordered that it be given to him. 59 Joseph took the body, wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, 60 and placed it in his own new tomb that he had cut out of the rock. He rolled a big stone in front of the entrance to the tomb and went away. 61 Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were sitting there opposite the tomb.”

We recently finished a series at Westview on the women who appear in Matthew’s Genealogy of Christ: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary. Through this series, I gained a better understanding of something oft-repeated in my childhood: that , “Christ died for our sins”. Below I argue that the courageous actions of outcasts reveals the sin and injustice upheld by insiders — the privileged and comfortable majority. Christ’s death reveals that salvation is a product of oppressed people’s resistance against injustice; such resistance calls the mainstream community to a better way of life.

To understand how Matthew connects Christ’s salvific work to the resistance of the women in Christ’s life, we’ll start by reviewing some general observations about women in Matthew’s Gospel; before, second, sharing a few of the lessons we learned at Westview about Christ’s grandmothers; and then, third briefly visit the episode where Christ is anointed by an unnamed woman. Finally, I will conclude by thinking about how the women waiting outside Christ’s tomb reveal what it might mean to say, “we are saved by the work of the cross”.

With these observations in mind, I want to turn to the salvific work of Christ’s mother and grandmothers. Tamar illustrates a common theme running through the work of these five women’s lives. Tamar is the daughter in-law of Judah, a brother of Joseph. She is a twice widowed by two of Judah’s sons. A survivor of sexual abuse, she is denied her rights according to Israelite law as a widow and a daughter in-law by Judah. In response, the oppressed Tamar presents herself to Judah as a prostitute and becomes pregnant. Upon hearing of her pregnancy, Judah orders her burned to death at which point she reveals that Judah is the father of her unborn child. Through her actions, Tamar lays bare Judah’s sin, that he has failed in his responsibilities to his daughter-in-law. Tamar’s courageous actions are a form of resistance; they call Judah to turn from his sin, and, more generally, display the poor state of widows in Israel. As a result, Tamar’s resistance against the oppressive patriarchy not only preserves her own future by securing her inheritance, but also gives both Judah and Israel a chance to turn from their sinful ways and begin properly caring for the most vulnerable.

Similar stories are associated with all of Christ’s grandmothers: Rehab is a prostitute who saves Israel’s spies in the city of Jericho. Ruth is a Moabite who is also widowed and uses her body to secure justice for herself and her mother-in-law, Naomi. Bathsheba is a foreigner, who is, by all accounts, raped by King David before he makes her a widow. David’s sin ultimately catches up to him because of these actions, and again it is through his relationship to Bathsheba that his sins are revealed and he’s held responsible. In one way or another these are stories of women revolting against the inherent abuses of patriarchy; and each story serves to convict the privileged majority in Israel of their sin. Each story of feminine resistance provides an opportunity for the privileged community to correct its sinful ways.

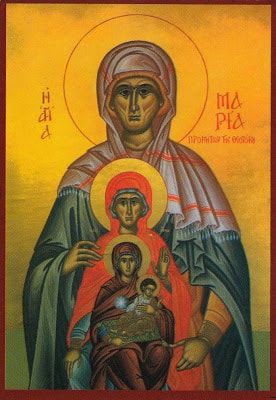

Christ’s own mother follows the same path of resistance as that of her ancestors. Being pregnant with Christ puts Mary in an extremely vulnerable position. According to Israelite law, as a young woman, pregnant out of wedlock, Mary ought to have been stoned to death. What kind of advice would you give Mary in her circumstance at the time? I would say, stay low, keep out of sight, don’t draw attention to yourself, hide your pregnancy. Of course this isn’t what Mary does. According to Luke, rather than believing she deserves death, Mary calls herself blessed and goes on to call out the very men who want her dead, saying,

“He has scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart.

He has put down the mighty from their thrones,

and has exalted the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich He has sent away empty.”

Mary calls for the mighty, those men with the power to decide whether a young woman like herself lives or dies, to be pulled down from their seats of power while exulting the lowly, those the powerful condemn to death.

Tamar resisted the injustice of her situation by dressing up as a prostitute and becoming pregnant, revealing Judah’s sin. Mary, similarly, resists by staying alive, carrying her child to term, and calling out all those men who see her as worthy of death. Never forget, Mary is Christ’s mother, and I believe that Mary goes out of her way to ensure that Christ is well versed in the lessons of his feminine ancestors.

In Matthew, like all the synoptic gospels, Christ's descent to the cross begins with the story of the unnamed woman with the alabaster jar who anoints Christ in preparation for death. The unnamed woman’s actions provoke criticism from the disciples, yet Christ praises her, telling the disciples that, “wherever this gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her”. Thinking about the role of women in Christ’s life, I’d like to speculate, that this woman understood well Christ’s ultimate goal. After hearing the parables, following Christ through his ministry, and seeing him perform signs and wonders, she identified something about Christ that his twelve male disciples could not. This woman with the jar of oil, like those female rebels in Christ’s family line, is in a better position to understand Christ’s work because she has intimate knowledge of oppression — a knowledge the disciples lacked as participants in the patriarchy. I’d like to believe that the anointing by this unnamed woman is Christ’s ordination into the plight of the widow, the poor, and the powerless. Like all of Christ’s mothers, he was about to betray the patriarchy and suffer as a consequence, a suffering the women in Christ’s life knew intimately. And perhaps the unnamed woman knew that the patriarchy would demand Christ's life, because they could not tolerate someone who deviates so far from the social script.

Immediately after this anointing, Judas decides to betray Christ, actions that set in motion a series of events that end with two women waiting patiently outside of Christ’s tomb.

How does Christ’s death save us from our sins? I believe that the effect of Christ’s sacrifice is no different from the sacrifice of his mother, his grandmother, and all the women who continue to suffer under patriarchy. It’s on the foundation laid by these courageous women after all, that Christ’s ministry receives breath. His suffering, like the women's suffering, reveals our sin, our need to confess, and the need for forgiveness. Just as the women’s stories call Israel to a new way of life, Christ calls us all to follow in his footsteps by confessing our sins, identifying with the oppressed, and smashing exploitive systems like the patriarchy.

Let us commit to memorizing Mary’s Magnificat while learning how to suffer with her, so no one is ever again forced to hang on a tree, to die in the streets, or be stoned for becoming pregnant out of wedlock.

Caleb Ratzlaff attends Westview Christian Fellowship in St. Catharines Ontario. He spends the majority of each day raising two toddlers. And when he’s not chasing his boys around the neighbourhood, he might be blogging at calebratzlaff.wordpress.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed